Kraftwerk’s laboratory

The Sound of Düsseldorf

Kraftwerk’s laboratory

The Kling-Klang studio on Mintropstrasse

What used to be Kraftwerk’s Kling-Klang studio has become a place for a special kind of pilgrimage. Hidden away in a courtyard, not far from Düsseldorf’s main train station, the place still gives off the same hermetic aura that has always been a hallmark of the band. Gerrit Terstiege embarks on a voyage into music history.

Photo: Thomas Stelzmann

There is a small, select number of recording studios that have achieved an almost mythical status. Visiting them inevitably evokes a mixture of reverence and melancholy. Essentially, you are searching for a time that has been lost. Sun Studio in Memphis only remains intact today because subsequent owners – including a hairdressing salon – made only minimal changes to its fixtures and fittings. Even the perforated acoustic panels that can be seen on famous session photos of Elvis or Johnny Cash were simply left on the walls. These days, it is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, as is the Muscle Shoals studio in Alabama, making both certified historical monuments. That means they are likely to escape the fate of New York’s Columbia 30th Street Studio, which was unceremoniously demolished at some point in the early 1980s. The former church with its 30 metre high ceiling provided a unique sound quality that can still be heard on legendary albums by Glenn Gould, Miles Davis, Dave Brubeck, Bob Dylan and Pink Floyd.

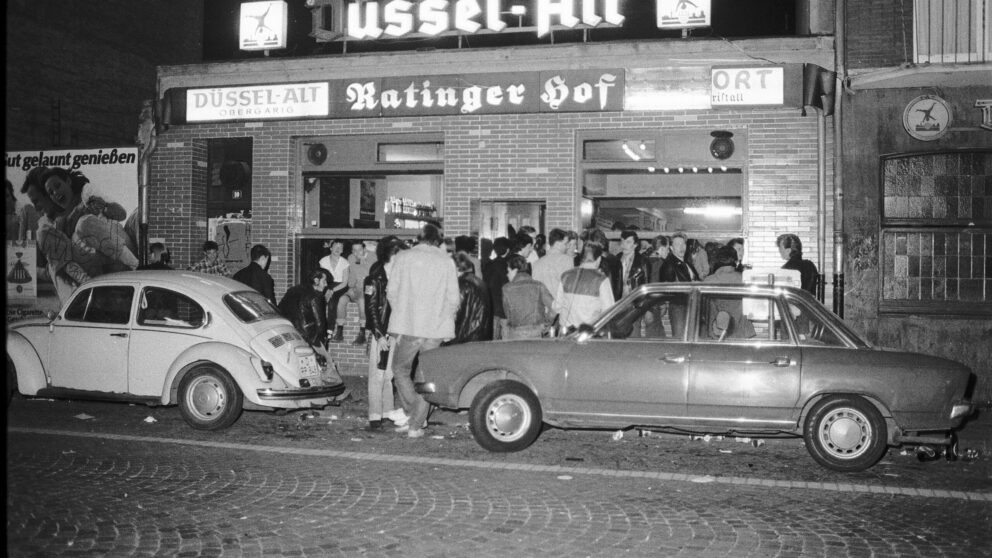

The birthplace of Düsseldorf’s music scene

London’s Abbey Road, the Hansa Studios in Berlin, Conny Plank’s converted pigsty in Wolperath – despite their utterly mundane, technical function, each of these places has an aura that stirs something akin to romantic emotions in music fans. Talking of romance, perhaps it is apt that Düsseldorf’s Mintropstrasse 16, the former location of Kraftwerk’s Kling-Klang studio, takes its name from Theodor Mintrop, a 19th century Romantic painter. But as I’m trying to get there by car, any romantic feelings evaporate fairly rapidly. The sat nav takes me through the narrow streets that surround Düsseldorf’s main station. It’s noisy and busy. With taxis and SUVs dodging the trams, I really have to concentrate on the traffic. Despite all that, I keep thinking of names from Düsseldorf’s cultural heyday as I’m driving along: Joseph Beuys, Blinky Palermo and Imi Knoebel, Marius Müller-Westernhagen in the Hühner Hugo snack bar, the dingy but seminal Ratinger Hof just behind the Academy of Arts, cradle of German punk and the place to be for anyone who was, or wanted to be, anyone.

‘Mecca of electronic music’

In 2014, Rüdiger Esch, former bass player of the band Die Krupps, published the book ELECTRI_CITY about Düsseldorf’s role as the ‘mecca of electronic music’. It contains contributions by a number of key figures from the seventies and eighties, some of whom have since died, such as Gabi Delgado and Klaus Dinger. Pro tip: If you’re not overly familiar with the Düsseldorf art and music scene of the time, you might want to start at the back of the book, which has brief biographies of the interviewees. Wolfgang Flür, Kraftwerk’s drummer from 1973 to 1986, provided a poetic foreword for ELECTRI_CITY. He wrote: “The magical river Rhine, with its heavily populated and industrialised banks, both attracts and incites people at the same time. It seems to harness huge creative powers. Its river bed constantly broadens until it flows into the North Sea; similarly the new trends that fuel the legend broaden and become mainstream: industrial, synth-pop, EBM, techno, house, electronica, ambient, drum ‘n’ bass, trip-hop, jungle, drone and dubstep. All these styles discard conventional song structures without taking away from their danceability. Based on our music, which concentrated on technology and the then-not-so-widely used computer, musicians and technocrats were able to become artists and pop stars.”

Finally! The voice of the sat nav drags me back to the present: “You have reached your destination. Your destination is on the left.” Only a few metres now separate me from the unremarkable building, its lower half covered in pale yellow tiles, presumably dating back to the early 1960s. The narrow driveway through to the courtyard resembles a dark, gaping mouth. As I park my car in the cramped courtyard, everything suddenly goes strangely silent. I stay in my car for a moment to collect my thoughts. Once again, I see images in my head. The back cover of ‘Ralf und Florian’ for example, which shows the two musicians at the Kling-Klang studio, surrounded by equipment from the very dawn of electronic music. The floor is covered in snaking cables, the brick wall behind Florian Schneider is bathed in an eerie green glow, while the cardboard squares behind Ralf Hütter are illuminated in red. A 1950s lamp with funnel-shaped lampshades throws yellow light on his keyboard, and their first names are spelled out in blue neon signs in the foreground of the picture. Other photos show the studio as a command centre, with the musicians as quirky lab technicians twiddling knobs, static like shop window dummies. Over almost four decades, the Kling-Klang studio took many different forms, defined by the size of the technical equipment at any given point. This evolved over time, as huge monstrosities turned into small laptops. The band is said to have stockpiled their old equipment in the basement, while keeping up to date with technological developments upstairs.

Kling-Klang kit on eBay

For a while, Rüdiger Esch had the key to the Kling-Klang studio, after Ralf Hütter stopped showing up there and Florian Schneider had also decamped. Esch knows the premises inside out – before they were renovated by subsequent tenants. “In 1970, Florian Schneider had rented this rather small room. And after he left the band, he stayed there for a few more years, until 2014, I think. He even continued to make music there, but I don’t know if any of it was ever recorded. At some point, he sold a whole lot of equipment from the Kling-Klang studio on eBay. He’d written to Ralf and asked him to collect the stuff, but it seems he never got a reply. The actual Kling-Klang studio was the first room on the left as you come through the door. The glass bricks that you can see from the outside are still the only windows. Later on, they rented some more rooms on the first floor. I bumped into Florian in the street a few times, because I used to have an office near here. We once had a long chat in an ice-cream parlour. That was great fun, he was from the Rhineland, after all. Once he’d left the Kling-Klang studio, a few tell-tale traces of the band remained, for example the numbered wall sockets.”

In 2009, Ralf Hütter had a new Kling-Klang studio built in Meerbusch. A newspaper reporter from the Rheinische Post did venture out there at some point, and asked around trying to find the studio, but without success. In some respects, the new version of the studio in Meerbusch is even more mysterious than the old one, simply because no one apart from the band’s current entourage has ever seen it. One fundamental difference between the old Kling-Klang and the other legendary recording studios mentioned – the converted churches and pig sties – is the fact that the guys from Kraftwerk were the only ones who had access to it. None of their musical decisions were ever influenced by pressures of time or money, everything remained under their control, and whatever happened behind those walls – crazy experiments, bitter arguments, tedious hanging about and sudden artistic breakthroughs – none of it ever reached the outside world. For many years, the studio was perhaps a sort of safe space for Hütter and Schneider, somewhere they could be undisturbed. And where time stood still. Despite its global impact and colossal musical significance, their oeuvre is actually fairly small. Eleven studio albums in 50 years is really not a lot. But then it’s never been about quantity. And perhaps at some point, the Kling-Klang studio became a dream space that fans were meant to fill with their own projections. With Kraftwerk, things are often not quite what they seem. For this band, play-acting and creating a strong image is an artistic endeavour on a par with musical achievement. Some historical photos appear to show other rooms crammed with technology. Perhaps a fictitious Kling-Klang studio?

By rights, it should have been heritage-listed long ago. Today, the fabled premises house makers of advertising films, recording engineers and sound designers. The former studio A is occupied by Moritz Staub and his company Staub Audio; the composer Martin Schütze works in the old studio B. So far, there is no memorial plaque. In a sense, the antiquated Elektro Müller sign above the entrance fulfils that function, as it allowed the band to remain incognito and work undisturbed for many years. Someone has put a traffic cone on the loading bay in front of the historical entrance door. A clear sign – casual and moving in equal parts. You might almost say romantic.

Photos:

Title image: Markus Luigs

Exterior view, street: Thomas Stelzmann

Other images: Düsseldorf Tourism

The Sound of Düsseldorf

Hundreds of visitors have followed in Kraftwerk's footsteps on the ‘The Sound of Düsseldorf’ tour. The digital exhibition on the Google Arts & Culture platform tells six stories about the city's influence on music. Düsseldorf has always been a meeting place for the avant-garde. The seeds of electronic music were sown here in the 1970s and 1980s, shaping pop right into the 21st century.

More on this topic: Six important places that are inseparably linked to “The Sound of Düsseldorf”